This post will walk through the basics around species, genetics, waves of breeding, and then step into what the F1 hybrid is, leaving space for a follow up which will explore propagation methods of F1 hybrid cultivars.

Whilst some of the information in these blogs has been acquired during my time in green coffee at DRWakefield, much of my knowledge within this piece has also come from my time spent studying at ZHAW under Sebastien Opitz et al., and thus credit is due. In addition, these and some future blogs will have been inspired by or somewhat catalysed by conversations with Aaron Davis at Kew.

Grota Funda, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Coffee Plant Kingdom and The Species Within:

We should start with the coffee tree itself, of which 124 species have been identified.

Two of these 124 species are of particular significance, as they compose most of the coffee which is consumed across the globe, and those two are C. canephora and C. arabica.

The usual definition of a species is a group of individuals that create fertile offspring however in the plant kingdom this is not as clear cut, particularly due to modern breeding methods as well as natural mutations in the field. In fact, C. Arabica is just that, being a cross that naturally occurred between two species: C. canephora and C. eugenioides.

Let us then first explore a bit about genetics and coffee, to be able to better understand why the event was so significant.

Genetics and Coffee

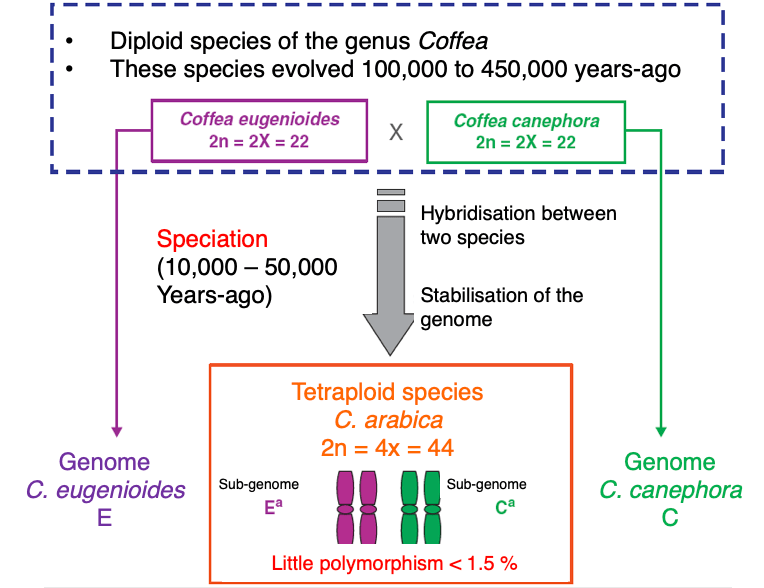

The first thing to understand is that most coffee plant species have 22 chromosomes, including Robusta, but Arabica has 44 chromosomes. How did this happen and why is it significant?

As noted above, C. arabica is the result of a spontaneous hybridisation event, where two separate species C. eugenioides and C. canephora crossed in nature and created a new species C. arabica. This example of an interspecies hybridisation also resulted in a special polyploidization event, where Arabica combined the two sets of chromosomes from its parents, resulting in a four-fold set known as tetraploidy. This is unique, as normally most species only have a double set of chromosomes; diploidy. The doubling thus caused a reduction in genetic diversity.1

Source: Lashermes P et al. Diversity and evolution of coffee trees in light of genomics, Cahiers Agricultures 21/2-3(2012)134–1422

How? Because only two genome genotypes, one from each parent, merged into one reducing diversity. This was then further reduced due to the fact that it was a handful of individual plants which were redistributed and bred worldwide during the age when coffee went through global expansion.

What then is a Genome? It is the entire set of the DNA instructions found in a cell. And what is a genotype? The sum of all possible genes, and thus the genetic makeup of the plant. The genotype decides every possible combination in terms of yield, resistance etc.

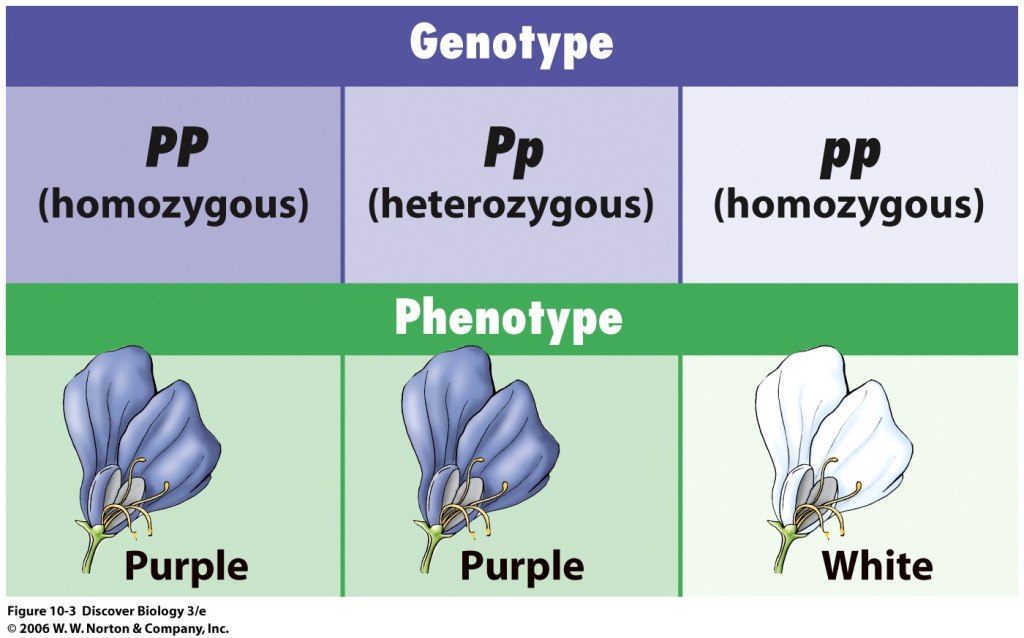

A genotype will have multiple possibilities, and so the way the genotype represents itself or is externally expressed is called the phenotype. If you consider the colour of a flower, the genotype will hold the possibilities for the plant, i.e blue or yellow, and the phenotype will denote the actual colour ie. blue. Interestingly, a phenotype can also be affected by the environment it interacts with!

A coffee plant usually has a double set of chromosomes which will have the same genes in them, but the information in each gene can be different as within each gene there are alleles. If the same allele is on both chromosomes, then it’s considered homozygous, and the allele is different than it is considered heterozygous.

Because Arabica has a double set of chromosomes, it theoretically can have 4 different alleles for the same gene!

Varieties and Cultivars

The next taxon one would note is that of its variety, as varieties exist within the taxon of species. These variety groups are identified by the fact they share genetic similarity, which suggests they will have similar characteristics. This means that these plants showcase traits that differentiate them from other plants of the same species. Variety is not to be confused with cultivar, as a variety refers to a ‘naturally occurring or spontaneously arisen variation within a species and tend to arise via natural selection, a genetic mutation or geographic isolation.3

A cultivar, the combination between the word ‘variety’ and ‘cultivated’, refers to one which has been artificially created rather than one that has arisen spontaneously. This means a cultivar does not have a natural origin, and will have been selected by a breeder because it has specific attributes that would be beneficial (i.e. high yielding or disease resistant). Simply put, a cultivar is human-made via genetic engineering, selective breeding or hybridisation.4

Nursery at Wahana Estate, Indonesia

Waves in Plant Breeding

Most of the commonly known ‘varieties’ out there today are actually cultivars, having been created for specific purpose such as increasing yield or cup quality. In fact, there are three main historical waves when it comes to breeding in coffee, and each have their own significance and aim.

First Wave: An Era of Productivity

Around the middle of the 20th century, the demands for volume in Brazil rose and so did the need for higher productivity. Because of the low genetic diversity of traditional Arabica cultivars which were being used in producing countries, there was a need to create new varieties which could adapt to these demands. This is the era where Caturra, Mundo Novo and Catuai were selected and cultivated, due to their potential for higher productivity. Catuai and Caturra, being dwarf varieties, were selected ‘for higher plant density while Mundo Novo was selected for higher vigour’. 5 These were then distributed across Central and South America, but have had susceptibility to disease which ultimately called for another wave and approach to selection and breeding.

Second Wave: An Era of Catimors

The emergence of diseases like Coffee Leaf Rust in Brazilian farms in 1970 called for a new approach to cultivation, one that looked toward solving this particular issue through creating cultivars that could be more resilient. It was around this time when a spontaneous natural crossing between C. canephora and C. arabica was discovered in Asia, commonly known as Hibrido de Timor. Because of its natural resistance to Coffee Leaf Rust, it become quite popular as it required less fungicides and thus lowered the cost of production. This attribute, alongside its higher yields, come from the C. canephora parent but along with those positive attributes were the less desirable ones; the cup quality of the Robusta was not as pleasing as the Arabica.

The solution to this was to cross the Hibrido de Timor back with Arabica varieties which have more desirable cup qualities, thus creating the era of Catimors which have since been distributed since the 1980’s. Some of those include Colombia (HdT x Caturra), Castillo (a selection of the Colombia cultivar), and Icatu (C. canephora x Red bourbon). All of these would be considered ‘interspecific hybrids‘, denoting the crossing between species.

Third Wave: An Era of Flavour and Pragmatism

In more recent years, and largely thanks to the acquisition of experience, information, and technology, breeding has been able to take focus toward combining all desired attributes alongside targeting that breeding toward terroir and environmental considerations. World Coffee Research are currently participating in multi-location breeding trials to find new varieties which work well and take into consideration the environment they will be grown in. At the same, trials in this era aim to combine high yields, disease resistance, and high cup quality, with resilience against more recent environmental pressures like temperature changes or droughts.

In addition, breeding is aiming toward widening the genetic diversity by crossing varieties from the Ethiopian landrace collection, due to that fact they naturally have more diversity than the others and thus can bring more to the final cup. This is because of what we spoke about earlier in this post, where we discussed the fact that most of what we know as Arabica today came from a small handful of plants. By contrast, many of varieties in Ethiopia went through natural breeding and mutation and thus these wild strains are more unique in their genetics. Added impact of environment further promotes this stated above, a phenotype can be impacted by environment.

The coffee I recently released, the F1 Hybrid of Centroamericano, acts as a perfect example of this as it is an intentional crossing between an high cup quality Ethiopian variety ‘Sudan Rume’ with the disease resilient T5296. For more on this please see: https://varieties.worldcoffeeresearch.org/varieties/centroamericano

So… what is an F1 Hybrid?

It’s actually pretty simple:

F stands for Filial

1 represents the first generation

Hybrid is offspring from the cross-breeding of two genetically distinct individuals, often aiming to combine the best characteristics of the two parents. There are two types of hybrids:

- Interspecies hybrid: cross between species i.e Timor hybrid is crossing between Arabica and Robusta species

- Intraspecies hybrid: cross between individuals of the same species, and thus at the variety level

This means that all F1 Hybrids are the first generation of a crossing between two genetically different parents, but some will be interspecies and some will be intraspecies. Regardless of whether inter or intra, the aim is to combine the best characteristics i.e higher yields, high cup quality, and disease resistance. Hybrids are particularly special because they tend to have much higher production than non- hybrids due to the heterosis effect. The heterosis effect is when a hybrid carries two different variants of a gene, leading to higher vigour and yield.

And what is special about an F1?

Because it is the first generation, it will exhibit qualities that are highly unique. These attributes will not necessarily show up in the offspring of the F1 (referred to as F2) due to segregation, and the new cultivar will continue to be unstable until its sixth or seventh generation…which will take around 15-25 years. This means that when you are sipping on an F1, you are likely experiencing something unique to it’s time and place, but more on that in a future blog!

In the meantime, I hope you are enjoying the F1 Natural from Costa Rica that I released a few weeks ago, and if you haven’t yet tried it I have a few remaining bags still available.

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Green Coffee From Tree to Trade’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022) ↩︎

- Lashermes P et al. Diversity and evolution of coffee trees in light of genomics, Cahiers Agricultures 21/2-3(2012)134–142 ↩︎

- Jamie Treby, ‘https://drwakefield.com/news-and-views/whats-the-difference-between-a-cultivar-selection-and-a-variety/‘ DRWakefield, 4 Sept, 2023 ↩︎

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lesson four: Plant breeding & variety’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022), p2 ↩︎

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lesson four: Plant breeding & variety’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022), p10 ↩︎

3 thoughts on “An Introduction to Breeding and Coffee Plant Genetics”