As we continue on our journey, exploring the innovations within green coffee via the propagation of new cultivars, we now take a look at how an F1 can be stabilised. In this blog, we look at how selection of the optimum plant takes place, why cloning is the optimum method, and what methods for cloning exist.

A short recap on how coffee cherries come about:

Although it would seem an obvious thing, it is important to remind ourselves of how we end up with the seeds which will produce the plants in the first place. For all coffee species, it remains the same that the plant’s flowers must be pollinated in order to produce fruit. A pollen grain from the stamen’s (male part) anther must get to the carpel (female part) and create a pollen tube for the sperm to travel down the style to the ovary within the flower. The ovules within the ovary are then fertilised by the sperm and develop into seeds, marking the death of the flower where the pericarp surrounding the ovules will then mature into what we consider the fruit.1

While many plants require cross-pollination, where pollen from one plant must be distributed on the style of another via a pollinator, some plants are able to self-pollinate! In these plants, pollen from the anther is distributed to the style of the same flower or a flower within the same plant. Whether a plant is able to self-pollinate depends on timing of the maturation of stamen and carpel, as they must mature at the same time, as well as their positioning in relation to each other.

Within the coffee species world, C. canephora requires cross-pollination while C. arabica plants are fully capable of self-pollination, making them unique. This is relevant as it impacts how propagation and variety stabilisation differ between the two, but more on that at another point.

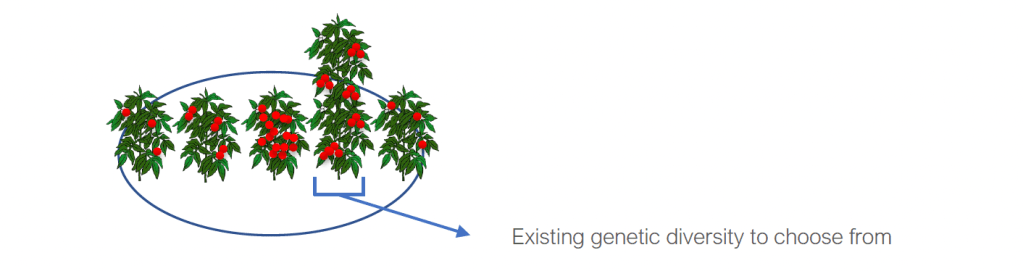

Producing genetic variation and selecting the F1:

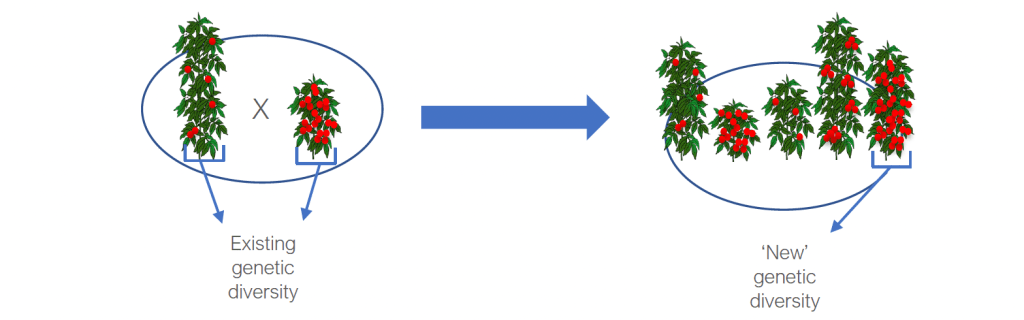

In a previous blog, we spent time discussing various waves within the cultivation of new varieties but all of them remain the same in their goal: to combine the genetic information from two parents to create an ideal combination of traits that solve a particular problem. There are a few ways to produce genetic variation, in order to then select the optimum plant which has the best combination of characteristics.

The first is called mass selection, where a large amount of plants from random seeds are planted and the offspring with the best traits are selected. This method is the simplest method but depends heavily on chance, however because the population is initially very heterogenous, the best adapted trees should perform best. Caturra was actually selected using this method. 2

The second option is the pedigree method, which is where controlled pollination between two selected individuals is performed, thereby forcing the desired combination of traits. ‘Breeders will cross two plants with complementary traits in the progeny. The goal is to select the offspring with the best phenotype that has ideally all the desired traits’.3 This controlled method will increase the success rate, and was used for the production of Catimors.

Stabilising the variety:

Both approaches will require stabilisation, so that the traits are fixed in the next several generations. To achieve this, self-fertilisation is commonly used in Arabica, however this process takes a minimum of 15 years!

15 years: 3 years for coffee plant to bear fruit + at least 5 offspring generations. F1,F2,F3,F4,F5

This is because the next generations (f2, f3 etc) will show segregation, where the offspring of the parents will not look like the parents/individual plants will showcase different characteristics of the parents (phenotype vs genotype). In order to avoid this longer 15-25 year process, clonal propagation can be used instead.

Clonal propagation:

There are a few methods which can be used in order to produce clones, though not all are equally optimum and some depend on whether the plant is a homogenous pure-line variety, a hybrid cultivar, or of the C. canephora species.

By Seed:

The first method is by seed method, which can only be used for pure-line arabica varieties that are homozygous and have little genetic variability otherwise the result will not be a ‘true to type’ variety. This method is not suitable for C. canephora as canephora require’s cross-pollination, so the resulting seed will contain 50% of each parent genetic material which will change the genotype. It is also not suitable for modern day hybrid cultivars, as this method will introduce the segregation described above and in the last post.

Cuttings:

An option which is possible for C. canephora and hybrids is cloning via cuttings. A plant is allowed to grow a suckers of orthotropic shoots, and these are then trimmed and placed in conditions where they will produce roots of their own. This process takes around two to three months, where these plants are then transferred to nurseries and is the most efficient method for producing a clone.

Grafting:

Another method is grafting, which is used to propogate a clone of two species. This is where a scion of the preferred species is grafted onto a robust species; ie a grafting a disease sensitive arabica onto a resilient robusta rootstock.4 New Varieties can also be grafted onto branches of old trees! This technique is often also used in wine- where European varieties are grafted onto American vines due to their disease resilience.

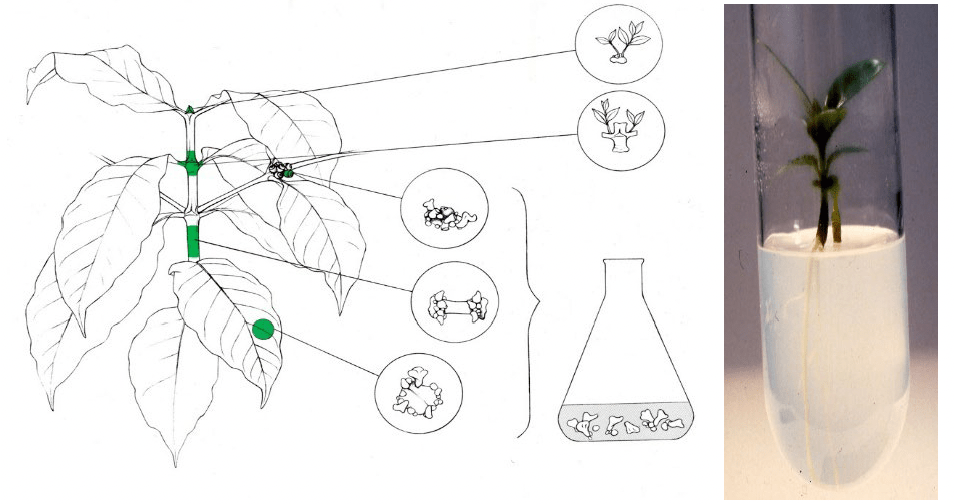

Microcuttings:

This is where coffee is grown from plant tissues such as the leaf, thus no seeds are needed. Small pieces of different parts of the coffee plant are taken and treated with hormones that act as growth regulators to produce new plants (see above image from Thomas Baumann at ZHAW). This method can be used for robusta or hybrid cultivars, as no seeds are needed, and can be achieved at scale.

Somatic embryogenesis:

The final method (see image above taken from a ZHAW lecture) is a modern in-vitro method. It can also be used to propagate Robusta and Arabica clones of F1 and F2 generations, and in high numbers. The embryo of the plant is derived from a single somatic coffee cell which is not normally involved in the production of embryos such as ordinary plant tissue, that is altered to grow into a new coffee plant. This is a highly technological method requires high levels of skill and appropriate labs in order to be successful, but if an option, offers a much quicker way to the propagation of these unique coffee plants that are identified in breeding programs.

Conclusion:

If you recently ordered my second release, the yeast inoculated washed H3 called ‘Pinapple Candy’, you will have had the pleasure to experience an example of a cultivar which was likely stabilised via cloning. As per Dr Ch. Montagnon’s wheel shows here, H3 is a clone of an F1. And while I am sure that was something you found interesting when you initially read about the coffee either on the card you received with your parcel, on my web-shop, or online here in a previous blog, you now understand just how interesting this topic can get! So interesting that I look forward to continuing this conversation and opening up forward thinking conversations with the third release…coming soon!

P.S. There is a small quantity of bags still available now- so get yours before they go.

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lifecycle: Fruit Fetilization’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022) ↩︎

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lesson four: Plant breeding & variety’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022), p17 ↩︎

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lesson four: Plant breeding & variety’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022), p23 ↩︎

- Sebastien Opitz, ‘Lesson four: Plant breeding & variety’ (Coffee Excellence, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021-2022), p224 ↩︎

2 thoughts on “An Introduction to Selection, Stabilisation, and Propagation”